MONROVIA — Democrats and Republicans can’t seem to unite on much these days, but if last Friday’s rally outside Farmhouse Brew in Monrovia is any indication, they do have at least one thing in common: They don’t want to see a data center come to Morgan County.

About 30 local residents gathered on a sweltering evening to hear a handful of speakers from across the political spectrum talk about why they believed Morgan County’s planned data center campus will be detrimental to the community.

After months of speculation, Morgan County announced its plans to construct a data center campus for an undisclosed company back in January.

The data center complex — with up to four proposed buildings — is planned on nearly 391 acres of land just east of Monrovia’s town limits. The campus will be positioned north of Ind. 42, east of West Union Church Road, south of Keller Hill Road and west of Antioch Road.

The planned data center has been met with near unanimous opposition from the community since it was announced, and for a variety of reasons. Some residents are concerned about the environmental impact a data center could have, others fear a data center will devalue nearby properties, and some are simply upset that several local officials know additional details about the data center but have withheld information because of non-disclosure agreements.

Friday night’s rally, organized by Backyard Farm Collective founder Christopher Lamberson and new Monrovia resident Alec Willis, touched on practically all of these grievances and more. Willis spoke with The Correspondent before the rally began, saying he felt “betrayed” after moving to Monrovia at the beginning of the year, as he and his wife had been hoping to live in a small community but had been blindsided when plans of a data center were announced.

“We come from small towns, and we thought (Monrovia) was exactly like both of our hometowns,” Willis said. “I feel misled. And as a member of the Republican Party, I feel betrayed.”

Willis was the final speaker at the rally, which lasted a little over an hour. The crowd, seated in lawn chairs under a makeshift tent due to the heat, listened to his story and his efforts to learn more information about the data center from local officials. Willis said he had spoken with Morgan County Commissioner Don Adams, who wondered aloud, according to Willis, why people continued to protest the data center, as it was going to happen “one way or another.”

“The county commissioners’ plan right now is basically ‘Trust me, bro,’” Willis said, referring to the county’s claim that a data center will be a financial benefit to the community.

“Republicans and Democrats are mostly on the same page on this issue,” he continued. “Unfortunately, it’s the Republicans (in the county government) who are doing this to us. Someone asked me recently, ‘Don’t you feel bad about going against your own party?’ And I told them loyalty is a two-way street.”

The county anticipates receiving approximately $750,000 in tax revenue from the data center in its first year, as well as an additional $250,000 for local school districts and government agencies. At $1 million, the data center will be the third-highest source of revenue in the county, behind the AES powerplant on Blue Bluff and the TOA automotive plant in Mooresville.

County officials hope the data center will eventually become the highest source of revenue for the county.

Bryce Gustafson from the Citizens Action Coalition — a center-left nonprofit organization, demonstrating the diversity of the data center opposition — spoke to the crowd about his various concerns with the data center, and was critical of the idea that the data center would be some economic “boon” for the county.

He and other speakers said they had learned from a reliable source that the data center would allegedly be owned by Google, though The Correspondent has thus far been unable to officially confirm this. Gustafson mocked the county for only bringing in a million dollars from Google, which is owned by the multi-trillion-dollar Alphabet company, comparing the tax revenue to “a nickel.”

Gustafson also expressed concerns about the potential electrical power strains that could come to Morgan County as a result of a data center, referencing the Amazon data center under construction in New Carlisle. That data center will use 2,250 megawatts of power, which could power one million homes.

Prior to the start of the rally, Lamberson passed around a flyer listing what opponents of the data center want in order to “protect” Morgan County. These demands include halting construction of the data center “until thorough review and community impact assessments are conducted,” ensuring ethical construction practices that prioritize environmental safety, guaranteeing fair compensation or protections for residents, and protecting the local ecosystem.

Data centers have significant environmental impacts, primarily because of high energy consumption and large amounts of water usage, amongst other factors. These campuses contribute to greenhouse gas emissions and can be a strain on local resources.

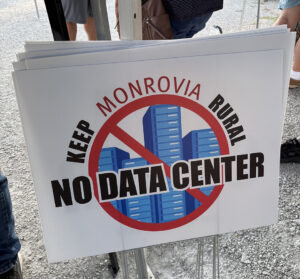

Ultimately, the main reason for opposition to the data center can be summed up by the slogan on the yard signs the organizers were selling at the end of the rally: “Keep Monrovia Rural.” Many in attendance sympathized with Willis’ story, as a large part of Monrovia’s appeal is the small-town feel of the community.

Data centers, with their propensity for noise pollution and the additional traffic construction will bring, are antithetical to small, peaceful Monrovia in the minds of these protesters.

For them, Google, and other “Big Tech” companies like it, are far too big for Morgan County.