MARTINSVILLE — The weekend before Mother’s Day in May 2024, Nikki Williams was walking outside to check her mailbox when her son called. He told her his 18-year-old sister was pregnant by her adoptive father who she had been living with since she was 6.

Williams cried and screamed.

“This is all my fault,” she kept repeating.

“This is all my fault.”

“This is all my fault.”

A tough period

Everything started in September 2010, when four of Williams’ children, all under 10 years old, were taken away from her due to her marijuana use and financial instability. On May 27, 2011, the kids were placed in a foster home, under the care of Sonja and Brian Stafford, who lived on a farm east of Eminence.

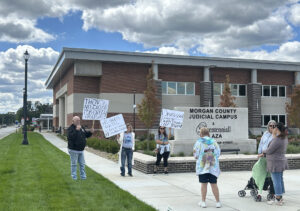

On Monday, almost 14 years later, Williams and her family held protest signs outside the Morgan County Judicial Campus in Martinsville as they awaited the pretrial conference for the case against the Staffords, who are facing more than 110 combined charges for child molesting, child neglect, domestic battery, obstruction of justice, and promoting human trafficking. Between 2008 and 2024, the Staffords fostered 32 children and adopted 11 of them — including four of Williams’ children.

When her kids were sent to live with the Staffords, Williams never expected this, she said. She was told the Staffords were upstanding citizens who had been foster parents for a long time. The Staffords lived on a farm, went to church regularly, and Williams’ kids were lucky to go to a family like that.

That’s the type of family Williams believed her kids were living with when she signed papers for permission to adopt in November 2011. The welfare office in Fountain County, where she lives, told her there would be an open adoption agreement until the children were 18, which would include visits twice a year, phone calls every month and letters every other month, Williams said.

After the adoption, the children were taken out of public school, Williams said. They were home schooled and allegedly spent almost all their time on the farm, rarely seeing other children their own age.

For the first two years, when Williams visited her children, she said Sonja watched them like a hawk and never let them spend time alone. During the first visit, one of her children called her “Mom,” she recounted. Sonja immediately corrected them, saying they couldn’t call Williams that anymore; they had to call her “mommy Nikki.”

During the visits, Williams said she noticed her children lost a huge amount of weight. The Staffords allegedly told her it was because the children were eating farm fresh foods instead of pop and sugar, but Williams left the visits concerned.

Then, out of nowhere, Sonja stopped allowing Williams to visit in 2014, Williams said. When Williams tried to figure out if Sonja was allowed to do that, she couldn’t find her record of her open adoption agreement anywhere. She still can’t.

“The only thing that’s on record is my consent to sign my rights away for my kids to be adopted. That means I’m no longer their parents, so there’s nothing I can do,” Williams said. “The only thing I could do is hire a lawyer to sue Sonja and Brian. I can’t afford to do that. I don’t have money to sue the state either.”

When the visits stopped, Williams made multiple requests for welfare checks, but nothing came from them.

Truth revealed

In 2020, Williams said the Staffords sent one of her daughters back because she was out of control and kept running away. Her daughter, who is now 21 but was 16 at the time, began telling her the abuse she suffered in the house and things Brian had allegedly done to her.

Williams and her daughter called and made reports about it, but they were told to stop or they would get in trouble for false reporting, Williams said.

When her son turned 18, he also came back to see her, she said, and she has since developed a really good relationship with him. He is now 22. Williams’ youngest daughter is almost 16. All Williams knows about her is she is with her new adopted family. Williams also has a 25-year-old daughter, who never lived with the Staffords and who also came to protest.

Williams also has a 19-year-old daughter who recently gave birth to a child fathered by Brian, her adoptive father.

Williams started making reports again when she found out about about her daughter’s pregnancy and her son told her about the physical, mental and sexual abuse the children allegedly endured in the Stafford house.

Williams said she called a sex crime phone number to report the pregnancy, and that’s when the cops and people from the welfare office finally came to the Staffords’ house in May 2024. But the Staffords weren’t indicted until December 2024.

Williams said she first requested a welfare check more than a decade ago. It’s been more than a year since she reported her daughter’s pregnancy. Now she still has to wait until January and March of 2026 for Brian’s and Sonja’s trials, respectively.

In the meantime, her 19-year-old daughter is still under Brian’s control, she said. When the Staffords were arrested, no-contact orders were issued to bar the defendants — who are now out on bond — from contacting the 11 alleged victims. Williams’ daughter began talking to her family every day, sending texts and making plans. But in February, Judge Brian H. Williams terminated the no-contact order, and the daughter stopped speaking to her family.

“This is severe grooming, and I don’t understand why the court doesn’t see it like that and how Judge Williams could think that it’s OK,” Williams said. “I just feel like by him dropping the no-contact order is him saying that their relationship is OK and normal.”

Williams’ family still texts the daughter now, but they only get a response once in a while.

A grandfather’s lament

Michael Shivey, Williams’ father, said he sometimes receives photos of the daughter’s new baby, who will be a year old in November.

The baby has four teeth now, Michael said, and she can sit in a high chair and crawl and eat Cheetos. He is seeing his great-granddaughter grow up over text.

Michael still very clearly remembers the day his grandchildren were taken away from Williams, the same night he was arrested. He remembers the police coming in and pointing tasers at him while two of his granddaughters clung to his legs.

“You’re not taking my babies nowhere,” he told the police.

But he didn’t see them again for more than 10 years.

They were his grand-babies when he last saw them, and now they have kids of their own. He was never given permission to visit them while they were at the Staffords, even in the beginning.

“But the thing is, they never forgot us,” Michael said. “That was the good thing. The older kids never forgot us.”

In 2020, when the first granddaughter came back to Williams, she went to Michael’s apartment and knocked. He opened the door, and she jumped and fell into his arms.

It was the perfect homecoming reunion after 11 years, said Tammy Spivey, Michael’s wife and the kids’ step-grandmother.

The past year has been very hard, Tammy said, but the family has been fighting against an unfair justice system from the very beginning. The kids should have never been taken away in the first place, she said.

Tammy said Williams’ kids were always well fed and had nice clothes and were well cared for. They played with the other children in the neighborhood, and Tammy’s own kids would go to their house every day.

“It was just a happy house,” she said. “I just hope one day we can become a whole family again.”

But Tammy wasn’t just protesting for her family and the alleged victims in the Stafford case at the justice center Monday. She wants to send a message to the justice system and stand up for all children suffering from abuse. If, after the Stafford case is over, there’s another child that needs help, Michael said they’ll keep congregating together to support them and raise awareness.

Back on track

From the beginning, Williams fought to get her children back — she took parenting classes, did therapy and took a mental evaluation. But it wasn’t enough.

She was told she wasn’t financially stable enough, and her evaluation diagnosed her with bipolar disorder. Years later, she visited her own doctor who told her it was a misdiagnosis, and she actually had PTSD and borderline personality disorder as a result of trauma she experienced throughout her life and everything that happened with her children.

In 2011, before her children were taken away, Williams admitted that she smoked a little weed. But everything changed afterwards. Williams said she didn’t care what happened anymore, became reckless and did other drugs. That’s when her mental health deteriorated, too.

But she turned things around for her family, and she has been off meth since June 2015. Then her oldest daughter got pregnant, and she continued working on herself and her relationship with her children.

Williams has 11 grandchildren now, and she’s very active in their lives. Just the day before, she attended the birthday party of one of her grandchildren.

Williams said her children are proud of what she’s doing to fight for them and for justice in the Stafford case.

On Monday, she drove over an hour to Martinsville and stood outside the courthouse for three hours ahead of the pretrial conference, only to be told once inside that nothing would be happening in court that day. It was just a filing deadline.

She left disappointed but resolved to come back in December for the next trial date.

“When it comes to crimes with kids, I don’t see how they can drag it out like this,” Williams said as she walked out of the courthouse. “I just feel defeated every time these things happen.”