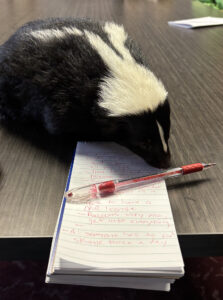

MORGAN COUNTY — Sylvia’s on the table now, and she begins to nibble at the reporter’s pen. Her movements are small, and she seems nervous to be the center of attention.

Anne Hurford is eager to hold Sylvia, but her sharp digging claws make an effort to resist being touched, and she drools all the way across the table before finally resting in Hurford’s arms.

“I like the personality of a skunk,” Hurford says. “They’re highly intelligent and very curious animals.”

Hurford used to have two pet skunks of her own, Jake and Elwood — named after the Blues Brothers due to their black and white attire — and she says they always stirred up trouble.

“They would take the pillows and the blankets off the bed,” Hurford says. “They unrolled the toilet paper. They’re like having a toddler.”

Hurford cradles this toddler inside The Correspondent’s office in Martinsville, petting Sylvia’s fine fur as she burrows into Hurford’s shirt. Sylvia and Hurford are joined by colleagues at the Trails End Wildlife Refuge, a Morgan County nonprofit that takes in orphaned and wounded wild animals, rehabilitates them if possible, and turns them back loose into the wild.

Sitting around the table is Jill Smith, the raccoon specialist who founded Trails End in 1986; “Skunk Julie” McLaughlin, who’s affiliated with Indiana Skunk Rescue; “Raccoon Julie” Burdine, the vice president of Trails End; and Jackie Cook, who specializes in possums.

Each of them spends what feels like every waking hour — and for them, that’s most of the hours in a day — attempting to nurse wild animals to be well enough to return to the wild. McLaughlin and Hurford have rehabilitated 88 skunks this year alone, and the critters usually stay as guests in the ladies’ homes while they recuperate.

“I’ve been sprayed five times this year,” Hurford says, something she shrugs off as if it was going to the dentist or getting an oil change.

The office was in no danger from Sylvia, though — the domesticated skunk has been de-scented, meaning the scent glands in her anus have been removed. Though the women from Trails End would encourage all to be unafraid, regardless.

“People are petrified to touch a skunk,” McLaughlin said. “That fear is way overblown.”

The same fears are often reserved for the other animals Trails End takes care of as well, from possums to raccoons. When these animals are dead and wounded on the side of the road, drivers may feel sorry, but they keep driving nonetheless. It’s someone else’s problem, they think to themselves.

Trails End is the someone else. They stop the car for wounded skunks, orphaned possums and injured racoons.

“This is what God put me here to do,” Burdine says, “to help God’s smallest creatures. You can hate raccoons, that’s fine. But you don’t have to be mean to them.”

‘If you don’t like walls’

In 1839, Charles Darwin remarked that skunks were “conscious of (their) power, roaming by day about the open plain, fearing neither dog or man.” None dared cross them, lest they fall prey to the skunks’ foul odor.

He wrote that long before the first automobile was invented, and well before the earth was covered in high-speed highways and byways. Today, the No. 1 predator of skunks are cars and the humans who drive them.

Skunks have been reviled by mankind for centuries, with the word itself not infrequently used as an insult. But not so for Hurford, who’s had pet skunks since the ‘70s.

For Smith, her favorite pets growing up were raccoons, animals popularly known for eating garbage and invading attics. Her father converted the family basement into a sort of racoon jungle gym, where the little bandits could run wild and play.

Even now, the animals usually stay inside the women’s houses while they’re being treated, something each of them has a state permit to do. Most of the animals are not pets, but they have permits for the pets, too — owning a pet raccoon is not exactly the same as having a golden retriever.

“Racoons are very mischievous,” Smith said. “They get into everything.”

“Racoons are destructive in a house,” Burdine adds. “But if you don’t like walls, carpet, flooring, or any of that stuff, you can have all the raccoons you want.”

The folks at Trails End are country people, and they’ve lived alongside these animals all their lives. If readers find their love of smelly skunks and rascally raccoons to be bewildering, they find the disdain and indifference of these animals to be just as alien.

“I humanize these animals,” McLaughlin said. “When I see an animal on the side of the road, to me, it’s no different than seeing a child hurt.”

And like a hurt child sees a doctor, these women tend to the animals, a job both time consuming and expensive.

Trails End has 98 animals in its care at present, and the cost to feed them alone is $4,245.24 a year. This is not to mention the bills they pay for medication, veterinarian visits, electricians, plumbers, maintenance supplies, the list goes on, and much of the funding comes out of their own pockets.

Then there’s the cost of cages or storage boxes with air holes for breathing, and also toys because, like any child, they “have to have enrichment.”

On top of the financial costs, rehabbing wild animals in rural Indiana has a physical toll. Larger organizations might have the manpower to divide labor evenly so that each worker gets proper rest, but the women at Trails End often work by themselves, and sleep is hard to come by when the animals need to be fed every two to three hours.

Trails End deals with a bitter truth: to care about something is “exhausting.”

Tears every time

Another bitter truth for Trails End is that not everyone can be saved.

Hurford said the organization probably loses 20 to 30 percent of the animals that get sent their way, and it never gets easier.

“It’s devastating,” Hurford said. “Those are the days that you just want to quit.”

She recounted spending three weeks on a “little girl” only to have to euthanize her in the end, as she wasn’t getting better.

“You have to remember that you aren’t God,” Burdine said. “You have to remember what you’ve saved.”

It probably becomes difficult to do that after a while, given the stress of the job. Their whole lives revolve around these animals: they don’t take vacations, they often can’t leave the house for extended periods of time, and they find few ways to relax. Those involved with Trails End sound like overworked ER doctors, which in some ways isn’t very different from what they do each day.

There is eventually a reward for doing the work they do, aside from the moral victory of the work itself, and they cry tears of joy every time it happens.

After all the hard work is done, and the animals are healed, they are freed back into the wild.

This often involves some travel — neighbors don’t usually want skunks or raccoons released near their properties — but it’s well worth it. If, indeed, skunks like Sylvia are just furry toddlers, then the rehabilitated animals venturing back into the forest are like dropping your kid off for college. They wander into a dangerous world, and you just have to hope that they’ll figure out how to navigate it.

“You’ve done God’s work,” Burdine says about releasing the animals. “And you just have to say, ‘Good luck, little buddy!’”

It’s a sweet moment for Trails End, a reprieve from the grind of mothering the helpless. Of course, another animal will always come around to replace the patient in the sick bed, but that’s the job. If they don’t stop the car for God’s smallest creatures, who else will?